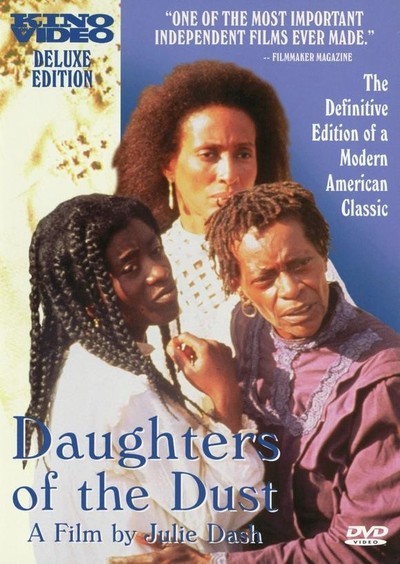

Daughters of the Dust

112 min | DCP

Julie Dash’s “Daughters of the Dust” is a tone poem of old memories, a family album in which all of the pictures are taken on the same day. It tells the story of a family of African-Americans who have lived for many years on a Southern offshore island, and of how they come together one day in 1902 to celebrate their ancestors before some of them leave for the North. The film is narrated by a child not yet born, and ancestors already dead also seem to be as present as the living.

The film doesn’t tell a story in any conventional sense. It tells of feelings. At certain moments we are not sure exactly what is being said or signified, but by the end we understand everything that happened—not in an intellectual way, but in an emotional way. We learn of members of the Ibo people who were brought to America in chains, how they survived slavery and kept their family memories and, in their secluded offshore homes, maintained tribal practices from Africa as well. They come to say goodbye to their land and relatives before setting off to a new land, and there is the sense that all of them are going on the journey, and all of them are staying behind, because the family is seen as a single entity.

“Daughters of the Dust” was made by Dash over a period of years for a small budget (although it doesn’t feel cheap, with its lush color photography, its elegant costumes and the lilting music of the soundtrack). She made the film as if it were partly present happenings, partly blurred racial memories; I was reminded of the beautiful family picnic scene in “Bonnie and Clyde” where Bonnie goes to say goodbye to her mother.

There is no particular plot, although there are snatches of drama and moments of conflict and reconciliation. The characters speak in a mixture of English, African languages and a French patois.

Sometimes they are subtitled; sometimes we understand exactly what they are saying; sometimes we understand the emotion but not the words. The fact that some of the dialogue is deliberately difficult is not frustrating, but comforting; we relax like children at a family picnic, not understanding everything, but feeling at home with the expression of it.

The movie would seem to have had slim commercial prospects, and yet by word of mouth it attracted steadily growing audiences, grossing over $140,000 in one month at the Film Forum in New York. People have told each other about it. “I’ve seen it three times,” a woman told me at the Film Center of the School of the Art Institute of Chicago. “I get something new out of it every time.” It is all a matter of notes and moods, music and tones of voice, atmosphere and deep feeling. If Dash had assigned every character a role in a conventional plot, this would have been just another movie—maybe a good one, but nothing new.

Instead, somehow she makes this many stories about many families, and through it we understand how African-American families persisted against slavery, and tried to be true to their memories.